Solution-Focused Brief Therapy is an excellent approach to help mitigate some of the mental health systemic challenges that have only worsened since the pandemic. I have developed a Solution-Focused Safety Assessment (SFSA) tool that has helped deal with the current mental health crisis, nurturing, harnessing, and sustaining hope when experiences may, at the moment, seem insurmountable. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) is a short-term goal-focused evidence-based therapeutic approach that incorporates positive psychology principles and practices and helps clients change by constructing solutions rather than focusing on problems. In the most basic sense, SFBT is a hope-friendly, positive emotion eliciting, a future-oriented vehicle for formulating, motivating, achieving, and sustaining desired behavioral change. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy embraces a strength-based developmentally informed trauma perspective that acknowledges individual and family capacity in the face of adversity. This approach offers an opportunity to assess and, to some extent, address the mental health and traumatic consequences of a pandemic for youth and families.

Solution-Focused Brief Therapy is an excellent approach to help mitigate some of the mental health systemic challenges that have only worsened since the pandemic. I have developed a Solution-Focused Safety Assessment (SFSA) tool that has helped deal with the current mental health crisis, nurturing, harnessing, and sustaining hope when experiences may, at the moment, seem insurmountable. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) is a short-term goal-focused evidence-based therapeutic approach that incorporates positive psychology principles and practices and helps clients change by constructing solutions rather than focusing on problems. In the most basic sense, SFBT is a hope-friendly, positive emotion eliciting, a future-oriented vehicle for formulating, motivating, achieving, and sustaining desired behavioral change. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy embraces a strength-based developmentally informed trauma perspective that acknowledges individual and family capacity in the face of adversity. This approach offers an opportunity to assess and, to some extent, address the mental health and traumatic consequences of a pandemic for youth and families.

Managing risk is the dominant paradigm in responding to suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the mental health field. Risk assessment focuses on ensuring the client’s safety and minimizing the danger of harm without treatment. By contrast, the Solution-Focused Safety Assessment (SFSA) examines the other side of the coin, confidence in the ability to keep oneself safe ( Lutz, A. B. 2014). It is a paradigm shift providing an additive dimension to conventional risk assessment. The SFSA creates a highly individualized action-oriented safety plan that incorporates individual and relationship resources (VIPs), coping strategies, reasons for living, best hopes for moving forward, and client needs based on their unique social context. The SFSA amplifies how clients have coped and managed to endure, even a little bit, the seemingly overwhelming distress that they have found unbearable at the moment.

I often am challenged with clients engaging in self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and behaviors in my practice. Incorporating a Solution-Focused Safety Assessment during times of crisis has been very helpful both for my clients, their VIPs, and managing my anxiety in these very stressful situations. Preparing clients for questions that evaluate their safety by explaining that these questions are routinely asked helps normalize their struggles, aiding them in feeling less alone. Framing questions about safety in the context of intense emotions and good reason communicate empathy. Asking clients about their good reasons for their decisions to harm themselves often reveals how clients engage in these behaviors because, in some way, the behaviors are helpful for them. The question does not condone the behavior but instead helps understand the client’s motivation and can help lead the conversation towards safer alternatives. When clients have contemplated suicide and not followed through, it is essential to ask what kept them from acting on their thoughts—asking clients their reasons for living guides the conversation towards their hopes, goals, and future dreams.

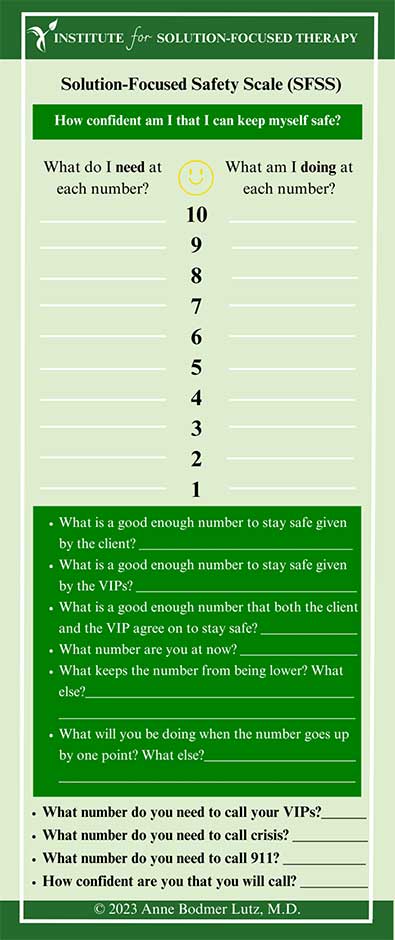

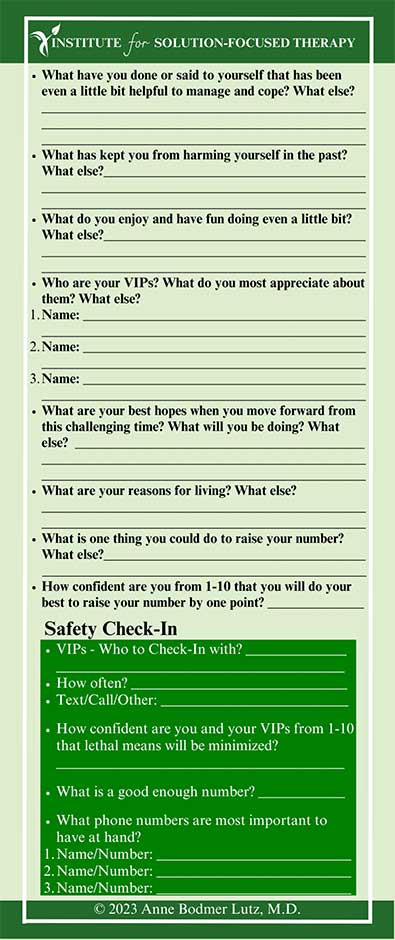

Below is a picture of the Solution-Focused Safety Assessment. To download this form as a PDF Please visit our Solution-Focused Tools.

Before the pandemic, I kept a stack of solution-focused safety cards available in my office. I would write the plan on the card with the client present and, if possible, also include their VIPs in the conversation. I have found that giving clients the safety card generated collaboratively provides a tangible reminder of the work we have accomplished together. It can cue them to their strengths, resources, and coping strategies in times of distress. I had one intellectually disabled client bring her tattered and worn down card with her to every appointment, telling me her safety number and proudly telling me what she had been doing to help her keep safe!

Since the pandemic, telepsychiatry has been a promising tool for children and adolescents in emergencies (Finlayson, B. T., Jones, E., & Pickens, J. C. 2021). Indeed, telepsychiatry has rapidly become a vital component in reducing safety risks related to coronavirus exposure. I have adapted the SFSA by completing it with clients using a shared screen. I then email or text the copy to the client, VIPS, and anyone they think would be helpful for them to have a copy of the SFSA plan. Because of the ease with coordinating teams remotely with telehealth, I have been able in many cases to include important VIPs that in the past would not have been immediately available in the development of a safety plan. I have invited parents, teachers, outside therapists, school counselors, emergency room nurses and physicians, and mobile crisis response teams, to name a few.

The Scope Of The Current Child Mental Health Crisis

Failure to address emergency mental health care impacts people of all ages resulting in increased health care costs and repercussions on local Emergency Departments (ED). Mental health workforce shortages and increased demand for services have required mental health professionals and organizations to devise innovative care delivery strategies. The pandemic has disrupted life for many months, an exceptionally long time for children and teens deprived of crucial connections to friends and school support networks. The pandemic has highlighted how we need to adapt our skills to emergency environments to creatively use available resources to meet the needs of youth and families. Solution-Focused Brief Therapy is an excellent approach to help mitigate some of these systemic challenges. With unprecedented challenges comes the requirement to adapt and utilize resources creatively to navigate horrendous situations. I have developed a Solution-Focused Safety Assessment (SFSA) tool that has helped deal with the current mental health crisis, nurturing, harnessing, and sustaining hope when experiences may, at the moment, seem insurmountable.

Many children and adolescents seeking treatment during the pandemic have a previous diagnosis of a mental health disorder, but others are in crisis for the first time (Kontoangelos, K., Economou, M., & Papageorgiou, C. 2020). For adolescents ages 13 to 18, mental health insurance claims doubled as a share of total medical claims during the height of COVID in 2020 (Ferget, Vitiello, Plener, and Clemens 2020). The shortage of psychiatric treatment beds and qualified staff existed well before COVID, but it has grown to alarming levels (Roadmap for behavioral health reform, Massachusetts). I recently witnessed a child awaiting a psychiatric bed for over 90 days! Not only is there a dire shortage of psychiatric beds for children, but there is a workforce shortage crisis. Hospitals are struggling to recruit and retain enough qualified staff, including mental health workers, social workers, nurses, psychologists, and psychiatrists (Behavioral health-related emergency department boarding in Massachusetts, 2021).

Many of the mental health failures and gaps have only worsened since the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID-19 is as much a challenge of how we will frame it from a mental health perspective as it is a public health crisis. The fragmentation of the mental health system in the United States has contributed to poor patient outcomes, lack of access to mental health treatment, and rising medical costs for all. Mental health patients and treatment providers have endured the COVID-19 pandemic, responded to the exacerbated mental health crisis, and coped with a chronically underdeveloped mental health workforce.

Children and young people account for 42% of the world population. As a practicing child psychiatrist, I am acutely aware that the COVID-19 pandemic represents an extraordinarily stressful experience for youths and families. The mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in youth have been diverse, ranging from the onset of stress-related disorders to the exacerbation of pre-existing mental health disorders, including increases in internet and electronic addictions, sleep disorders, and depression. As the death toll rises, numerous children and families are grieving a loved one in a context that is often highly traumatic, unable to participate in rituals to help them grieve and honor the loved ones in their lives. The lock-down has also interfered with culturally accepted mourning processes, further aggravating unresolved and complicated grief.

Caring for children with special needs such as autism spectrum disorders, intellectual disabilities, developmental disabilities, chronic complex trauma, and attachment disorders has created even more of a challenge for families and caregivers to access much-needed services. The severity and outcome of mental health conditions have worsened because of delays in prompt diagnosis and treatment (Rousseau, C., & Miconi, D. 2020).

Parents and caregivers attempting to work remotely or unable to work while caring for children at home have only worsened disparities between high and low socioeconomic status families. In particular, women leaving the workforce while caring for their children has strained families even further. The economic impact of the pandemic has further added to the pressure families have endured leading to upsurges in domestic violence, substance abuse, depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Recognizing the extent to which family mental health affects youth mental health, we are compelled to appreciate the cross-generational stress caused by the pandemic (Leeb, R. T., Bitsko, R. H., Radhakrishnan, L., Martinez, P., Njai, R., & Holland, K. M. 2020).

Workforce Mental Health Shortages Impact On Children’s Mental Health

Emergency departments (EDs) are often the first point of care for children experiencing mental health emergencies, particularly when other services are inaccessible or unavailable. The pandemic has highlighted how we need to adapt our skills to emergency environments to creatively use available resources to meet the needs of youth and families. In recent years an ever greater number of patients find themselves seeking care for psychiatric illness in the Emergency Department (ED) . 6-10% of ED visits present for psychiatric illness. These visits weigh heavily on the ED system. Patients with psychiatric illness occupy 42% more time than non-psychiatric visits in the ED (McEnany, Ojugbele, Doherty, McLaren, & Leyenaar 2020). A survey of 1400 ED directors by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) found 79% having psychiatric patients boarding in their EDs, with 62% reporting that no psychiatric services occur while patients are boarding in the ED. Even when services are available, there are prolonged waiting times to see clinicians. ED boarding carries a high-cost burden. In 2017, mental and substance use disorder emergency department (ED) visits had service delivery costs of more than $5.6 Billion, representing more than 7% of the $76.3 billion total ED visit costs (Karaca and Moore, 2020).

A Case Example: How The Solution-Focused Safety Assessment Tool Can Be Helpful In Responding To The Mental Health Crises With Children and Families In The Emergency Department

The following is a fictionalized case vignette based on real clients I have treated in crises. The vignette uses a family case within the emergency room to illustrate how to incorporate a Solution-Focused Safety Assessment with children and families experiencing a mental health crisis.

Case Vignette Summary

Sara is a 17 y/o girl who I had been treating as an outpatient. She has been diagnosed with PTSD, Autism, School avoidance, and depression. Her mother called me, learning that she had taken a week’s worth of her medication and was now being evaluated in a crowded emergency department (ED) by the psychiatric mobile crisis team. Her mother was anxious about her staying in the emergency room and waiting weeks for a child psychiatric inpatient bed to become available. She was also concerned about Sara being exposed to distressing conditions within the ED, including agitated patients, medical emergencies, COVID infection, and under, inadequately trained staff regarding the mental health needs of children. Her mother, just recovering from breast cancer treatment, was understandably cautious about bringing her to the emergency room, knowing the risk of COVID and having an immunocompromised status. She knew about the long waits to obtain a psychiatric inpatient bed – often many weeks, and how this would further exacerbate her daughter’s fragile condition.

Sara lives with her mother, a single parent and her 8y/o brother. Her mother has a history of breast cancer, currently in remission. Her brother is treated for ADHD and PTSD. Her father has severe substance use issues, has been in and out of jail, and had his parental rights terminated due to the severity of abuse inflicted on the family. Sara, her brother, and her mother endured significant trauma for many years resulting in complex trauma.

Sara had challenges preceding the pandemic, including school refusal, bullying, and school failure. The situation for Sara only worsened during the pandemic as she would often spend hours in her room online, staying up at night, disrupting her sleep, increasing her anxiety, depression, and isolation even further. Sara had other episodes of depression, including thoughts of hurting herself during the pandemic.

Sara was very challenging to engage using telehealth. She would often refuse to join the sessions, and if she could tolerate them, her video was off, and the conversations would last 5 minutes. As a result, sessions often focused on supporting and increasing her mother’s confidence in helping her navigate the immense challenges of having 2 children with significant mental health needs while also managing her stress, including her medical condition and being the primary caretaker and financial provider for her children.

Sara was taking several medications and required some medication adjustments. This required necessary blood work, which she refused to do, preventing other more helpful pharmacological interventions.

While in the ED, the mobile crisis team would do a 5-minute telehealth check-in stating the bed search continues. The ED provided no other treatment or interventions due to limited resources and staffing shortages.

Solution-Focused Interventions in the Emergency Department

I began by providing her mother with many “for you” statements regarding how challenging and scary this must have been for her. I bridged this with a coping question asking her how she has been able to get through this moment to moment. I complimented her mother for taking the necessary steps to get her daughter the help she needed while managing all her other demands as a single parent. Given my relationship with Sara and her mother, I offered telehealth sessions to both her and her mother while in the ED. Sara was exhausted and asleep, unable to meet. Her mother was desperate to meet and develop a safety plan that would get Sara out of the ED as quickly as possible. I discussed with her mother her best hopes and what she knew Sara needed. I also considered what my best hopes were for her and the family so I could feel confident she was safe enough to be discharged home. Her mother’s best hopes that would tell her Sara was ready to be discharged home were for her to agree on daily safety check-ins, manage her daily expectations at home including sleep schedule, participating in telehealth appointments and tutoring for school, going on a walk daily and managing a healthy electronic diet in a good enough way. She also hoped she would stay out of her room and help with some daily family chores. My best hopes were to know the safety plan was “good enough” and that Sara could get the necessary medical tests to adjust her medications more effectively. I also wanted to provide a stress test while in the ED to ensure Sara could manage safely upon discharge to home.

I went through the Solution-Focused Safety Assessment with her mother and the ED nurse with the suggestion that this be filled out with Sara when she was awake. In addition, we discussed the need for Sara to know the expectations at home and the plan if she had challenges meeting these expectations. We agreed that she would not be discharged without the written safety plan, expectations, and necessary medical tests completed. In addition, the SFSA plan would need to be discussed with the ED team and mobile crisis team, ensuring their agreement with this plan.

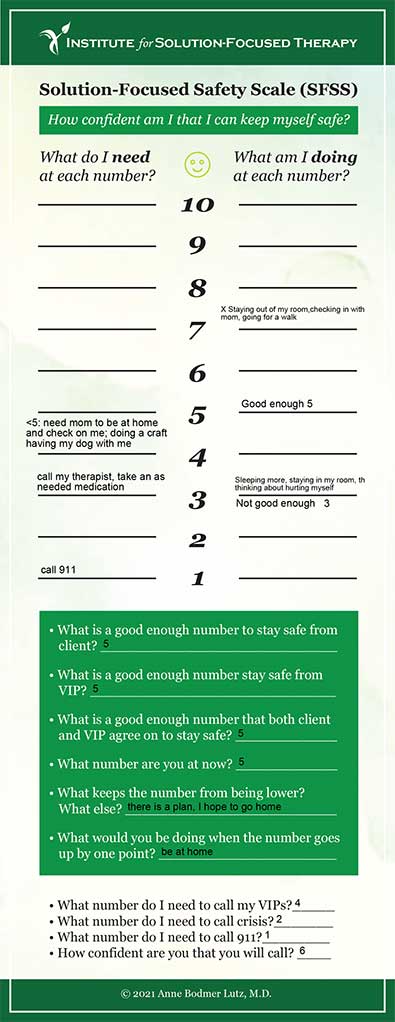

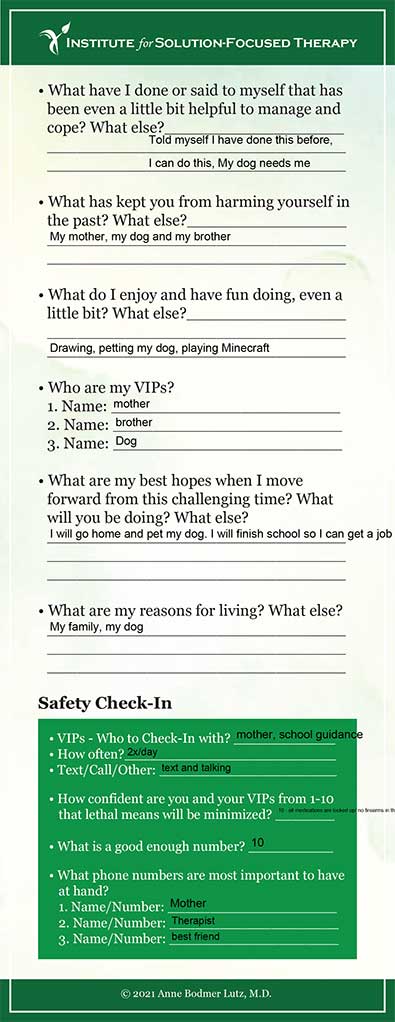

I have attached the SFSA plan based on this vignette.

Sara was discharged and I had a follow-up appointment with her four days later. She was on the zoom with a video camera on and pleased to tell me she had gone on a hike with her mother and brother. She was getting some of her school work done, going to sleep, and waking up at more consistent times. We had begun a medication adjustment, and she reported tolerating the adjustments 7/10 (good enough) and was hopeful the new medication would help her anxiety and depression. I complimented both Sara and her mother on the many ways they handled this very stressful and challenging situation, including getting her blood work done, managing electronic expectations and sleep, and checking in daily with her mother regarding her confidence in her ability to keep herself safe from 1-10.

Below is the Safety and Recovery Plan co-developed with Sara and her team while in the ED that also functioned as a stress test, helping to increase the team’s confidence that she was ready to be discharged home.

Stress Test

- Meet with your therapist and doctor, including participating in the zoom meetings, staying logged in with the video

- Take a walk for 15 -20 minutes every day.

- Work on getting to bed and waking up at the same time every day

- Work on developing an electronic health diet

- What do you know is a healthy electronic diet?

- What do you know is a healthy youtube diet?

- How confident are you from 1-10 that you can maintain a healthy electronic diet?

- What would be a good enough number?

- Complete the Solution-Focused Safety Assessment with your mother and review it with the ED staff and your outpatient clinician/doctor before discharge

- Complete the necessary medical tests

How confident are you that you can complete the expectations from 1-10?

How confident is your mother that you can complete these expectations from 1-10?

What would be a good enough number?

Resources

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline number is: 1-800-273-8255

For the National Text Hotline, text the word TALK to 741741

Locally, the crisis line for Call2Talk is 508-532-2255. Or text C2T to 741741

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention has additional resources at https://afsp.org/find-support/

References

Bartels, S. J., Baggett, T. P., Freudenreich, O., & Bird, B. L. (2020). Covid-19 emergency reforms in Massachusetts to support behavioral health care and reduce mortality of people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 71(10), 1078–1081. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000244

Behavioral health-related emergency department boarding in Massachusetts. Retrieved October 7, 2021, from https://www.mass.gov/doc/behavioral-health-related-emergency-department-boarding/download.

Chen, S. (2020). An online solution-focused brief therapy for adolescent anxiety during the novel coronavirus disease (covid-19) pandemic: A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04355-6

The cost of mental illness: Massachusetts facts and figures. (n.d.). https://healthpolicy.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/MA-Facts-and-Figures.pdf.

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for Child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

Feinstein, Robert. (2021). Crisis intervention psychotherapy in the age of covid-19. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 27(3), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1097/pra.0000000000000542

Finlayson, B. T., Jones, E., & Pickens, J. C. (2021). Solution-focused brief therapy telemental health suicide intervention. Contemporary Family Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-021-09599-1

Karaca, Z., & Moore, B. (n.d.). Costs of emergency department visits for Mental and Substance Use Disorders in the United States, 2017: Statistical brief #257. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved October 7, 2021, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32550678/.

Kontoangelos, K., Economou, M., & Papageorgiou, C. (2020). Mental health effects of covid-19 Pandemia: A review of clinical and psychological traits. Psychiatry Investigation, 17(6), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2020.0161

Leeb, R. T., Bitsko, R. H., Radhakrishnan, L., Martinez, P., Njai, R., & Holland, K. M. (2020). Mental health-related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 1–October 17, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(45), 1675–1680. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3

Lutz, A. B. (2014). Learning solution-focused therapy: An illustrated guide. American Psychiatric Publishing, a division of the American Psychiatric Association.

McCluskey, P. D. (2021, August 7). This is a crisis on top of a crisis’: Patients with mental illness are waiting for overwhelmed hospitals to treat them. Boston Globe.

McEnany, F. B., Ojugbele, O., Doherty, J. R., McLaren, J. L., & Leyenaar, J. A. K. (2020). Pediatric mental health boarding. Pediatrics, 146(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1174

Pearlmutter, M. D., Dwyer, K. H., Burke, L. G., Rathlev, N., Maranda, L., & Volturo, G. (2017). Analysis of emergency department length of stay for mental health patients at Ten Massachusetts emergency departments. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 70(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.005

Pediatric and adolescent mental health emergencies in the emergency medical services system. (2011). PEDIATRICS, 127(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0522

Roadmap for behavioral health reform. Mass.gov. https://www.mass.gov/service-details/roadmap-for-behavioral-health-reform.

Rousseau, C., & Miconi, D. (2020). Protecting youth mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A challenging engagement and learning process. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(11), 1203–1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.007